West Papuans in exile: A conversation with Corry Ap

December 25, 2018

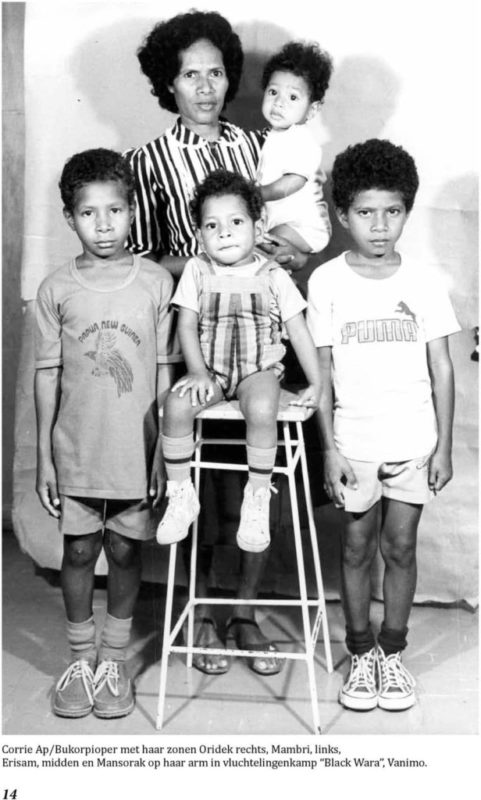

Corry Ap is the widow of assassinated West Papuan cultural leader, musician, and anthropologist Arnold Ap. She is also the mother of Oridek Ap, Head of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua EU Mission, and Raki Ap, Spokesperson for the Free West Papua Campaign. Now living in exile in the Netherlands, we recently sat down with Mrs. Ap to have a conversation about her very long and complicated journey.

PART I Growing up Melanesian

Free West Papua Campaign (FWPC): It’s interesting that you have lived during the transfer of power between the Dutch, the U.N.’s short administration, and witnessed all 57 years of Indonesia’s occupation of West Papua. What was your family life like growing up before all of that happened?

Corry Ap (C.A.): I grew up on Biak island with my parents, my 2 brothers and 3 sisters. My father taught primary school, and Sunday school. Strong community. Happy times.

FWPC: Today is Christmas. What was Christmas time like for you as a child?

C.A: Oh Christmas was a very happy time. We would start preparations in September or October. We didn’t have a (pine) tree. We would decorate the banana trees.

FWPC: How did you spend Christmas day?

C.A.: We would always start at church service. Then gather for lots of food and singing.

FWPC: You speak so many languages now, what was you first language at home?

C.A.: Biak and Malaya (what is now Bahasa/Indonesian)

FWPC: Is BIak what you call your indigenous language?

C.A.: Yes, it’s just the “Biak” language.

FWPC: When your family would sing Christmas songs did you sing in your native language?

C.A.: Yes mostly in both Biak and Malaya.

FWPC: What kind of schools did you go to?

C.A.: First primary school then to a Dutch run school for women. At the school for women I was trained to be a midwife, and after graduation I started doing that work since 12 years old.

FWPC: When did you first leave Biak?

C.A.: As a teenager I went to work at the Dutch military hospital in Sentani (Sentani is in Jayapura, now the capital of Indonesia).

Part II Indonesian invasion

FWPC: At that time in West Papua there was a lot of political turmoil happening between the Dutch and Indonesia. Were you aware of what was going on?

C.A.: I was a teenager. We were just being young, living and preparing under the Dutch to be an independent country.

FWPC: How did you find out Indonesia had invaded West Papua?

C.A.: It was announced on the radio and newspapers.

FWPC: At what point did the invasion come into your life to affect you personally? What was your first sign up close when you realised it was happening?

C.A.: We saw the helicopters. Being at work at the hospital, wounded Indonesian soldiers started to be brought in. Our supervisor, a Dutch military doctor, told us we were to treat everyone, even them. So that’s what we did.

FWPC: How did you find out that the United Nations had given Indonesia administration of West Papua and the Dutch would be leaving?

C.A.: At work. We were brought in and the Dutch explained it to us.

FWPC: Did you stay and work under the Indonesian administration when it changed over?

C.A.: Yes. We kept doing our jobs like we were trained to do.

FWPC: Did things stay the same when Indonessia started to run the hospital?

C.A.: No. Things declined quickly.

FWPC: How so? What was the first sign that things were changing?

C.A.: Well, under the Dutch, the hospital was very clean. Very structured. It started to be not taken care of and we had no medicines to give people.

FWPC: How did things change outside of the hospital?

C.A.: The stores quickly ran out of food and supplies. There was nothing to buy. There was no food.

FWPC: What did Indonesia do about it?

C.A.: They gave out government rations. We had to eat what they gave us.

FWPC: Being that you were only around 16 and 17 years old at the time, what did you think about your situation and what might happen to you?

C.A.: All we could think about was voting for our independence. We were holding out hope for the referendum.

FWPC: All you could do was just ride it out until you could vote in the Act of Free Choice?

C.A.: Yes. We were waiting for referendum.

FWPC: By the time of the Act of Free Choice in 1969 you were eligible to vote. Was there any instruction about how and where to vote? Did any representatives from the United Nations tell the people when the vote was going to happen?

C.A.: No. Nothing. We thought we might be able to vote at work, but no one gave us any information.

FWPC: Did you find out anything about how to vote in the newspaper or on the radio?

C.A.: No.

FWPC: Where were the Papuan leaders who had made up the New Guinea Council that was formed to take over and run an independent West Papua? Were any of those leaders out communicating information to the people about voting?

C.A.: The Dutch had taken all of the leaders to Nederland. There was no one left to organise the people.

FWPC: Instead of holding an open vote for hundreds of thousands of Papuan people eligible for voting, we know now that only 1,026 men were handpicked to vote for Indonesian rule. How did you find out the vote had happened and that you were staying under Indonesian occupation?

C.A.: On the radio.

FWPC: What was the reaction of Papans to the news?

C.A.: Papuan resistance started right away. So did Indonesian intimidation, imprisonment, and killings.

PART III Becoming the AP family

FWPC: During this time of civil unrest and panic in West Papua you found love and met the man you would marry. How did your husband come into your life?

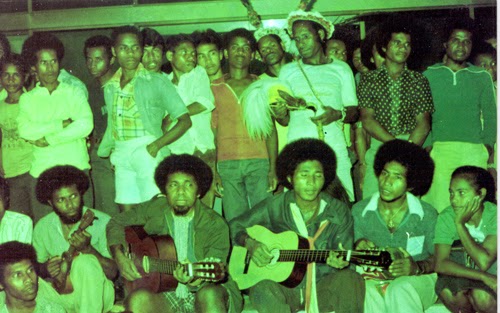

C.A.: As medical professionals we would go to tend to the prisoners. That’s where we met, in the jail. At this time he was already involved in speaking up about independence in his music. He was being targeted by Indonesian police and in jail because of his songs. His songs would give the people hope, and their identity. He would tell them they were not Indonesian.

FWPC: How old were you both when you got married?

C.A.: I was 19 and he was a year older than me.

FWPC: You would get many more years of seeing your husband in prison. What was family life like when he wasn’t in jail.

C.A.: Our house was full of our 3 boys, with people visiting and working on music. As an anthropologist he was very dedicated to preserving our cultural identity and the languages of West Papuan People. People would come from all over so he could transcribe their native words and put them in song. Our family would travel to their villages too.

FWPC: He had such an intellectually rich life. He curated the museum at Cenderwasih University, hosted a radio show, and traveled with his band Mambesak. What would happen when he would be arrested?

C.A.: Over the years he was jailed for different lengths of time. Sometimes 3 months. Sometimes 6 months. We didn’t know how long he would be there, but me and our children would go to visit him every day.

FWPC: Do you remember what his charges were?

C.A.: No. There were no [formal] charges. They would just take you and lock you up.

FWPC: Did he have a lawyer, or did you go to his court dates or any trial?

C.A.: No. There was nothing like that. No lawyer.

FWPC: After a decade of going through this cycle of being arrested and held in jail, when did things change to becoming dangerous for him?

C.A.: It was always dangerous, but it became clear they were going to kill him and possibly our whole family. I wanted all of us to leave together, but it was too dangerous to stay. He told us we had to go. He had made arrangements for people to pick us up and take us out of West Papua. We went to see him in the jail at 4pm, then we were in a car being taken away by 6pm.

FWPC: You had 3 boys and were pregnant too?

C.A.: Yes.

FWPC: What was your goodbye at the jail like?

C.A.: We knew when or if he got out of jail he would come to us. He wanted us to take our family to a place where our sons could become educated and return to fight for West Papua. He told our boys “Right now you don’t understand what is happening, but someday you will.”

In 1983 Arnold Ap was arrested and imprisoned along with fellow musician Eddie Mofu for singing freedom songs and on suspicion of being sympathetic to the independence movement. While in custody he was shot in the back and died from the fatal wound on April 26th 1984. There was no investigation into his murder, and to this day the Indonesian government has not acknowledged any wrongdoing, nor prosecuted anyone for his death.

Part IV Life in exile

FWPC: You only had 2 hours until you were in a car to be taken out of West Papua. Did you have time to pack?

C.A.: No. just a small bag of clothes for the boys..

FWPC: Family photos? Valuables?

C.A.: No. Just the one bag, the little bit of money we had, and our lives.

FWPC: Where did the car take you?

C.A.: We were put into a boat with 3 other families to go to Papua New Guinea. They gave us 3 days worth of food and pushed us out into the dark.

FWPC: What happened when you arrived in PNG?

C.A.: We made camp with the other families we were with and spent the first night sleeping in the jungle. Then the next day I went to an administration building.

FWPC: Run by the PNG government?

C.A.: Yes. They sent us to Blackwater camp. They gave us a plot of land to build a house on. You could stay, but you had to build your own house.

FWPC: You were pregnant and had 3 boys under the age of 8. How did you build a house?

C.A.: With the other families in the camp. We all helped each other.

FWPC: Did you have your baby in that house?

C.A.: No. The baby (Raki) was born in hospital. As a midwife I would help deliver the babies when there was no time to make it an hour away to the hospital, but if there was time the police would take you.

FWPC: The PNG police would drive you an hour away to have your baby?

C.A.: Yes. There were police there to protect the camp. When someone needed care they would take you to the hospital and also give you a ride back.

FWPC: At the camp were you waiting for your husband?

C.A.: Yes

FWPC: How did you find out he wasn’t coming to join you?

C.A.: Another family arrived at the camp and brought the message that he had been killed by Indonesia.

FWPC: You weren’t able to bury him, or have a funeral. What did you do?

C.A.: The people in our village all came to our house. We cried, and sang, and prayed together. I met my husband in a jail, and we had to say goodbye in a jail.

FWPC: How long did you stay in the camp after that?

C.A.: For one year then we went to Nederland.

FWPC: What made you decide to leave PNG?

C.A.: I wanted to honor my husband’s wishes for the boys. He wanted them to go to a safe place and receive a good education.

FWPC: How did you get to Nederland?

C.A.: At the time the Red Cross was there. You could apply for asylum.

FWPC: Could you afford plane fare for a family of 5?

C.A.: No. The Red Cross provided our fare.

FWPC: Where did you live when you got to Nederland?

C.A.: A niece of my husband’s was already here so we were able to stay with her.

FWPC: Was there family around to teach your sons their father’s music?

C.A.: We have family here, but they mostly learned from listening to cassettes he made.

FWPC: All 4 of your sons are now very active in the independence movement with 2 working as organizers and the other 2 having stepped up front as public leaders. What did you tell them growing up that led to their activism?

C.A.: I always tell them to feel the spirit of their father is to carry on his work.

Part V: The Ap family today

Tonight Corry Ap is spending Christmas in Nederland with her and Arnold’s 4 sons and spouses, and their 6 grandchildren. The Ap brothers continue their work as leaders within the independence movement to Free West Papua, and as the caretakers of their father’s musical legacy.

Before his assassination Arnold Ap asked a relative to bring a cassette recorder and his guitar to the jail. He penned his final song ‘Mystery of life.’ Sensing his impending death, his last known words to the world were captured in song as he sang …

What I am longing for

What I am waiting for

Nothing but freedom

If only I were an eagle

I’ll fly high

My eyes slip

But dear what a sad fate of the bird

Becoming prey

Being killed eventually

What I am longing for

What I am waiting for

Nothing but freedom

What am I longing for

What I am waiting for

Nothing but freedom

Arnold Ap’s music remains popular and inspirational to West Papuans. His songs of freedom continue to be covered by artists all over the world.

Jacob Rumbiak, Spokesperson of the United Liberation Movement for West Papua singing ‘Mystery of life’ in the original language it was written